THE ENEMY

Making Of

Par Fabien Barati – Part 3/7

Tel Aviv & Gaza

Setting up

The first shoot took place in Tel Aviv. It was the most straightforward location in terms of logistics, and to find soldiers to interview. Jean-Gabriel and I met Karim and Selim in the Israeli capital on May 5th, 2014.

As soon as we arrived in our Airbnb where the four of us were staying, we emptied the living room of its furniture to transform it into a recording studio.

First task on the agenda: install the white background. It would help us cut the background from our photos, if necessary. But above all, it provides uniform lighting on the combatants. This is extremely important to properly integrate the combatants into the final virtual set. Lighting equipment was then arranged and adjusted, taking this constraint into account.

The cameras were installed as follows: three of them set up on the left, middle and right, captured the combatants in a full-body shot. The last camera was used to film their faces in a close-up.

Finally, I had two Kinects installed on either side of the room to capture movements.

After a few tests, we were ready to welcome the first combatants.

Capture studio in a Tel Aviv apartment.

Step 1: Interview

Israeli soldiers arrived in turn. They were fitted with microphones and then invited to stand in the centre of the room. Jean-Gabriel adjusted the equipment to their height.

Karim, with the help of a translator, began the interview. He asked various questions about their lives and inspirations. They answered in their own language.

Karim did a fantastic journalistic work. Finding the right candidates, earning their trust so they would open up, asking the right questions; this is what imparts The Enemy such a great impact when you listen to the combatants.

During this phase, we filmed the soldiers with all four cameras at the same time, recording their voices with a microphone and their movements with the Kinects.

This is exactly what was said and done in these interviews that we would later have to recreate in 3D. This is what the users of The Enemy would ultimately experience.

Step 2: Photos

The second step was to take photos of the combatants’ entire body. Not a square centimeter was to be omitted; we had to be able to reconstruct each combatant in 3D thanks to these very high-resolution images. There was no room for guesswork.

We also wanted to obtain high-quality textures, critical to achieve realistic clothing and skin models.

It was a complicated task on paper because the combatants had to take poses that, without being difficult, could at times seem ridiculous to them. It was hard to predict their reaction to this situation.

Indeed, we asked them to present their palms, sides, the inner sides of their feet, the top of their head, their eyelids with closed eyes, and worst of all, their teeth with their lips rolled up around gums!

No problem in the end, Karim was able to put them at ease.

Step 3: 3D scan

I then scanned the combatant, who had to stand perfectly still, using a Kinect connected to a laptop. On screen, I could see the 3D reconstruction of their body in real time. It is a very noisy yet interesting source to process the combatant’s overall shape.

I was then able to show them the result, an interesting approach that would put them face to face with their virtual double.

Step 4: Backup

Once the soldiers left, the next few hours were spent saving and duplicating all the data captured. We emptied the memory cards on several hard disks that became our war chest.

Gaza

The following day, Karim, Selim and Jean-Gabriel headed to Gaza to interview Palestinian combatants. For lack of a press card, I did not accompany them; I followed their adventures remotely, which turned out to be rather dangerous and full of unexpected occurrences. For instance, they were blocked at the border on their way back, and had to wait two days to get through.

In the meantime, I fixed up the apartment. As soon as they returned to Tel Aviv, we were able to leave for Paris without any issue.

We were about to know if the source material we had captured was truly usable!

Realistic virtual characters

General representation

The realism with which the combatants are modelled is a critical parameter for The Enemy. Their representation and their virtual double must be entirely credible; otherwise, the user would dwell on their flaws rather than on their message.

Creating a perfectly realistic virtual human being is a tall order, especially when the person they represent must be recognizable. The slightest imperfection can highlight their virtual nature, and make it awkward to stand face to face with an “almost human”.

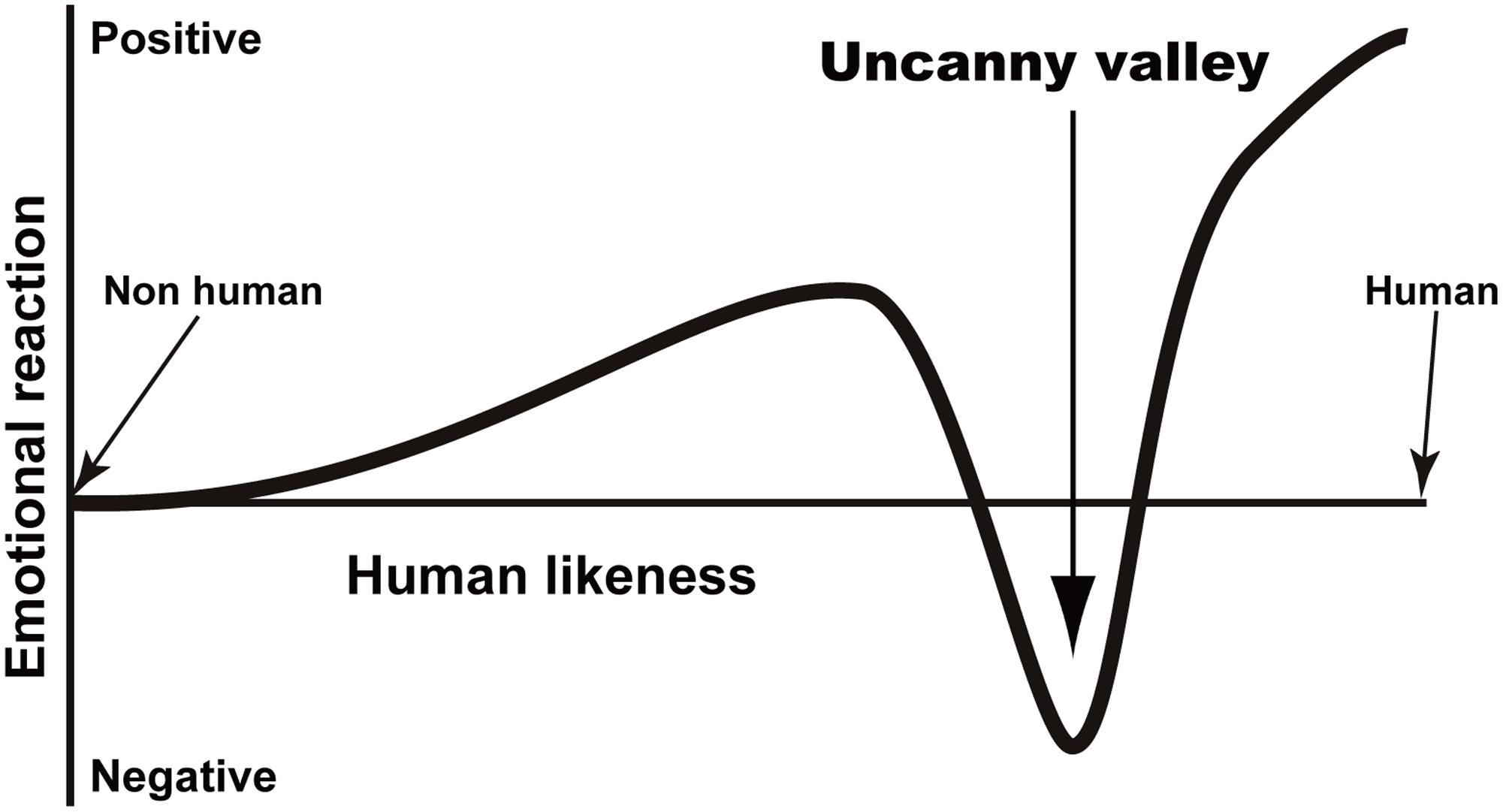

This is an issue known as the uncanny valley: the closer you get to realism without reaching it, the further you increase this feeling of discomfort. That’s why it was absolutely necessary to achieve total realism.

Theoretical representation of the “uncanny valley”

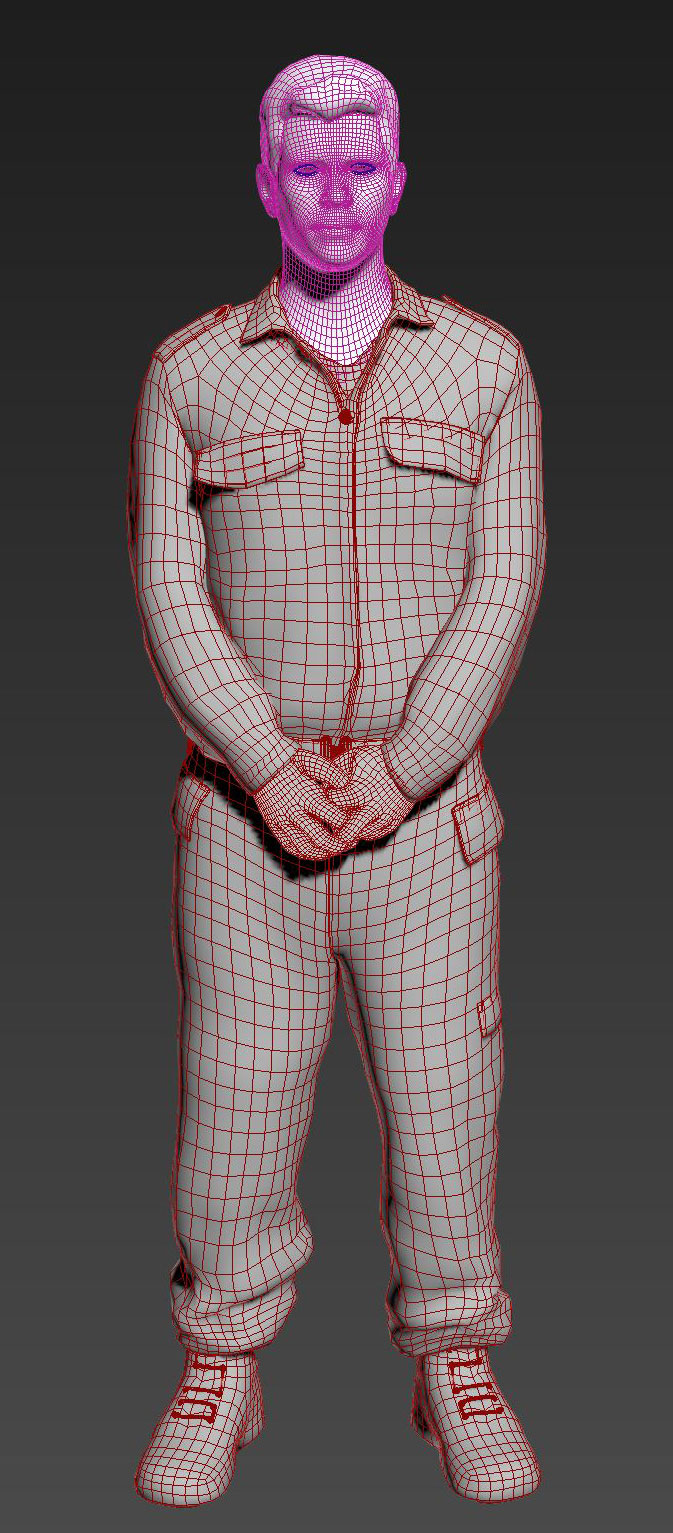

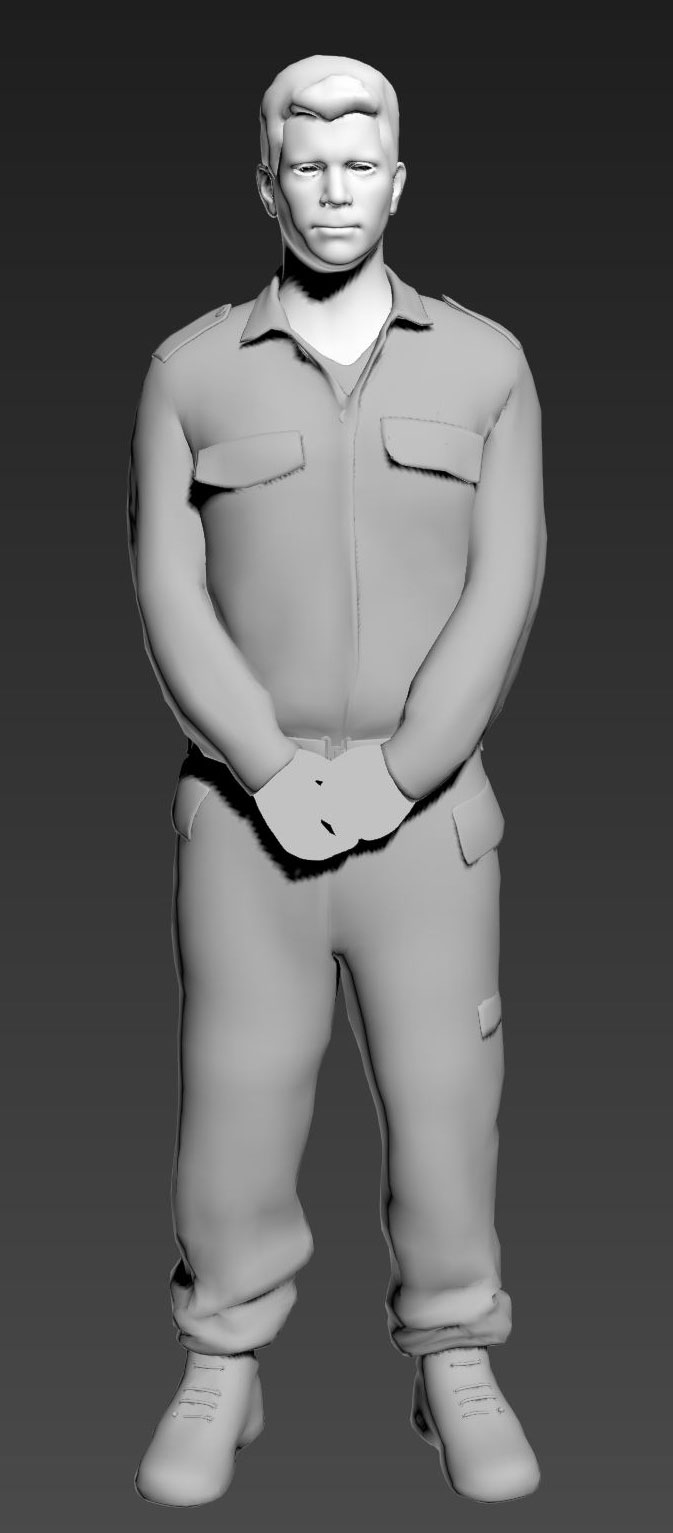

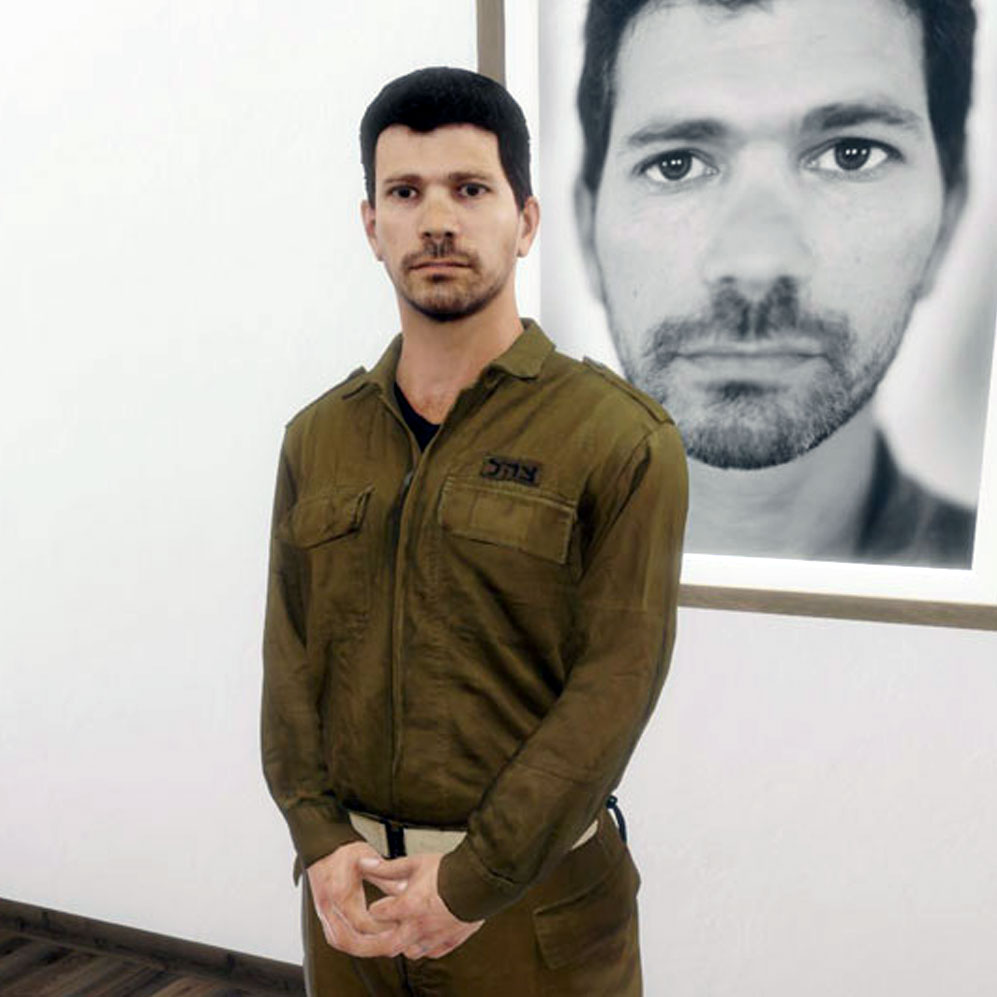

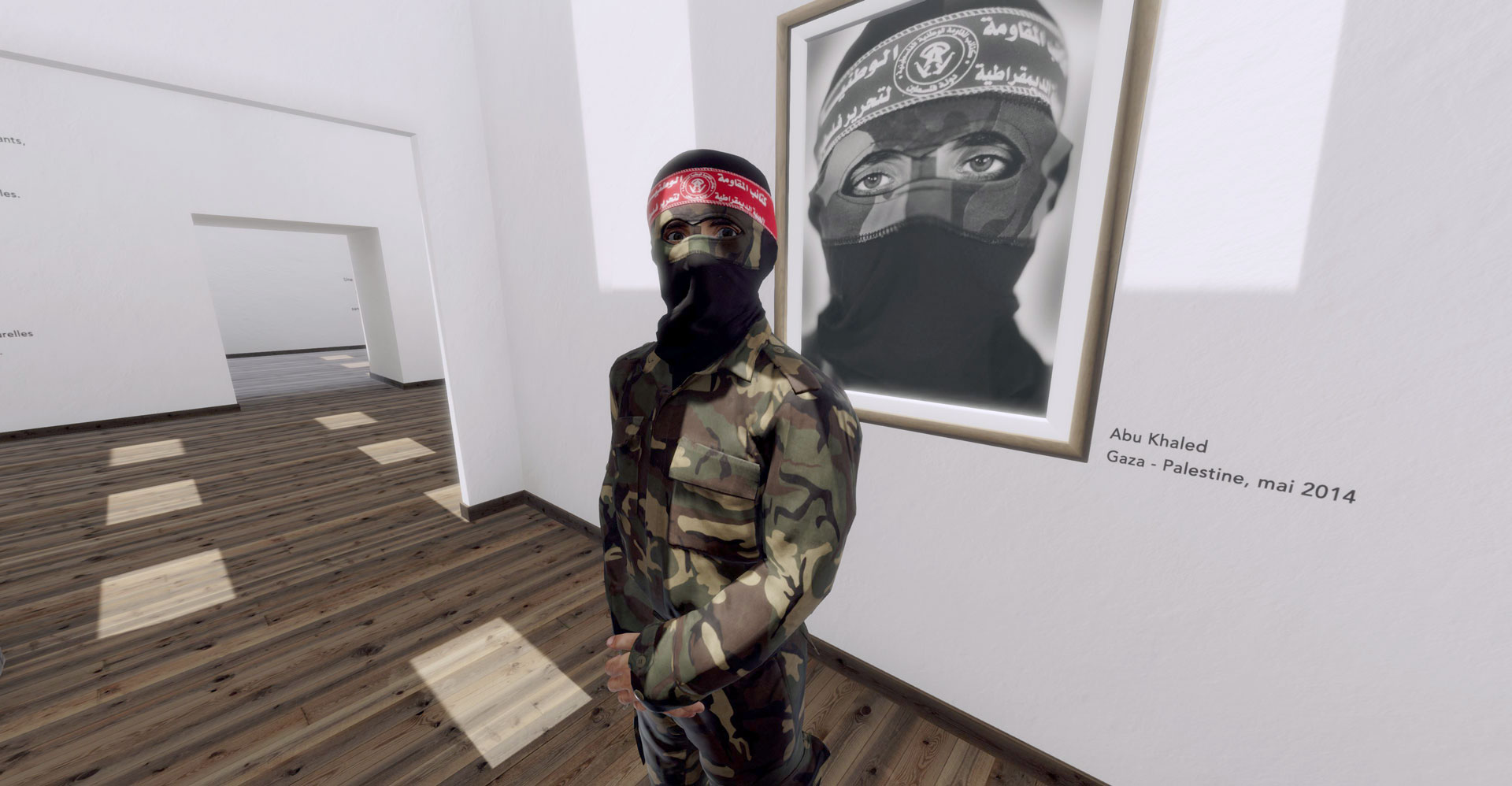

The 3D modelling of the combatants was entrusted to Vanessa Jorry and Jean-Baptiste Sarrazin, who are both 3D artists at Emissive. They used the various sources collected in the field to render Gilad and Abu Khaled. Although not perfect, these sources proved to be more than enough to achieve a very high level of realism.

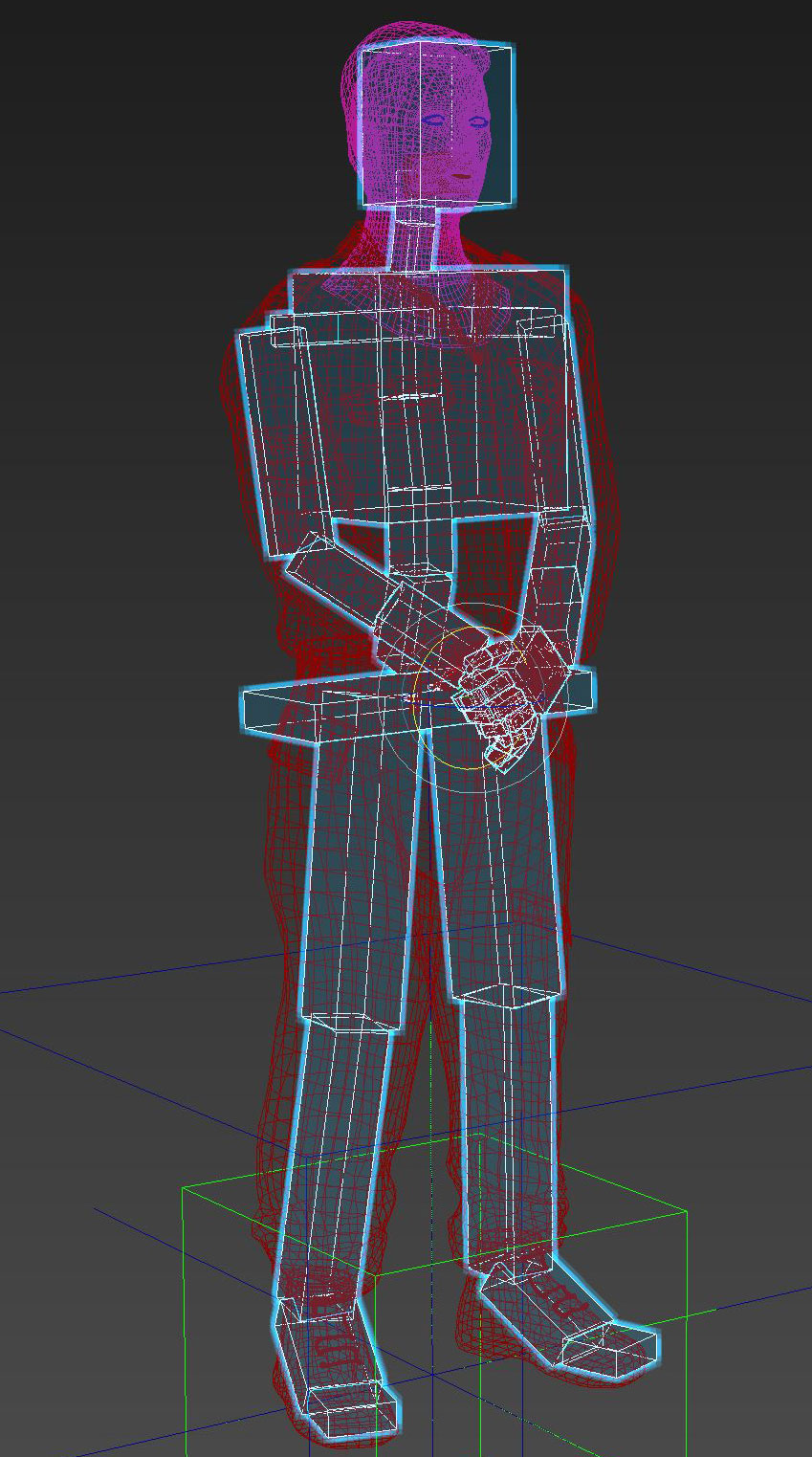

Virtual combatants must be perfectly realistic

Movement

Movement is also a critical parameter. Of course, we had to go beyond the robotic gestures that so often distinguish virtual characters. We had to perfectly model the gestures that the real combatants made during the interview, going so far as to represent the micro movements of Gilad’s leg, the Israeli soldier. Clotilde Steffen, our animator at Emissive, did a remarkable job despite the fact that motion capture wasn’t on the cards.

Clotilde skinned and rigged the virtual combatants, meaning she created virtual bones within their bodies and heads. She then moved these bones to animate the combatants by synchronizing with the captured videos. Every poses put end-to-end give a complete animation.

Unfortunately, the sources extracted from the Kinects weren’t satisfactory, so we only used the videos.

To animate the combatants’ faces, we used the software Faceware, which – from the close-up videos of the combatants’ heads – was able to render visemes over time (a viseme is a facial pose that corresponds to a particular sound). We obtained a series of visemes synchronised with the combatants’ voices. Although not perfect, it saved us a lot of time. Clotilde then took over each animation and provided a very precise work to render their faces’ natural movements and micro movements.

Virtual combatants’animations are a perfect copy of the real movements

Parametric animations

For the purpose of immersion and involvement, the combatants also perform gestures targeted at the users or reactions to their behaviour. For example, they can move backwards if you get too close, or follow you with their eyes. These parametric movements (which are not pre-set by an animator but by a mini artificial intelligence) must also be perfectly realistic.

For instance, eye tracking requires playing on the angle of the eyes, the angle of the head (which differs from that of the eyes), the speed and limits of their rotation, acceleration and deceleration.

With regard to the overall quality of virtual characters, I found the result satisfactory when users started being afraid to approach the combatants. They seemed as threatening as they were in real life. It was the starting point to discover their humanity.

Abu Khaled in The Enemy

MAKING OF

Emissive

71 rue de Provence

75009 Paris – FRANCE

+33 1 49 53 09 26